The following article was printed in McCLURE'S MAGAZINE

MCCLURE'S MAGAZING

VOL. XXXVIII DECEMBER 1911 NO. 2

THE MONTESSORI SCHOOLS IN ROME

THE REVOLUTIONARY EDUCATIONAL WORK OF MARIA MONTESSORI AS CARRIED OUT IN HER OWN SCHOOLS

BY

JOSEPHINE TOZIER

[Four years ago Maria Montessori, an Italian physician and educator, opened the first "House of Childhood" (Casa dei Bambini) in Rome, and began to apply her revolutionary methods of education to the teaching of little children. Her work has set on foot a new educational movement that is not only transforming the schools of Italy, but is making rapid progress in other countries. In June, 1911, Switzerland passed a law establishing the Montessori system in all its public schools. Two model schools were opened in Paris this September, one of them under the direction of the daughter of the French minister to Italy, who has studied with Montessori in Rome. Preparations are being made to establish Montessori schools this year in England, India, China, Mexico, Korea, Argentine Republic, and Honolulu. In the United States, schools have already been started in New York and Boston, and Montessori has received applications from teachers in nearly every State in the Union who wish to study with her in order to apply her methods. To meet the demand for instruction, Montessori will open a training class in Rome this winter for teachers from England and America. EDITORS.]

Sections and Links:

"The external world," says Madame Montessori, "transformed by the tremendous development of experimental science in the last century, must have as its master a transformed man. If the progress of the human individual does not keep pace with the progress of science, civilization will find itself checked."

Madame Montessori, who is an anthropologist of European reputation as well as a teacher, has adopted the inductive methods of experimental science to insure the development of the individual, under freedom, to his highest capacity.

"The conception of freedom which must inspire pedagogy," she says, "is that which the biological sciences of the nineteenth century have shown us in their methods of studying life. The old-time pedagogy was incompetent and vague, because it did not understand the principles of studying the pupil before educating him, and of leaving him free for spontaneous manifestations. Such an attitude has been rendered possible and practical only through the contribution of the experimental sciences of the last century."

The methods of this new system of pedagogy are exactly the same as are adopted by all modern investigators in the field of biology.

Deftness and Bodily Poise a Result

of the Montessori Sense Training

In the first place, Madame Montessori tries to give the child an environment that liberates his personality; she places him in an atmosphere where there are no restraints, where there is no opposition, nothing to make him perverse or self-conscious, or to put him on the defensive. His personality is thus liberated into free action, and the thing he is expresses itself.

Secondly, by her system of sense training she develops in the child a sense of his relation to his material surroundings and a facility in accommodating himself to them. As a result of the sense training, he learns to manage his body deftly, to walk without stumbling, to carry without dropping, to touch objects delicately and surely – in short, to move among the material things that surround him, whatever they may be, with ease and freedom, and with the least possible fret and wear to his spirit and to his body. Every element of embarrassment and self-consciousness is overcome, and he inevitably prefers harmonious action to the discord by which the untrained and awkward child so often tries to hide his inadeptness.

Thirdly, Madame Montessori tries, through her sense education, to reach and to stimulate the intellect itself. Through the child's interest in the materials with which he works, she leads him to purely intellectual concepts of form and the relation of numbers.

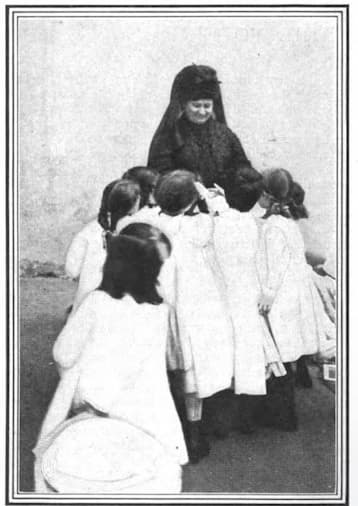

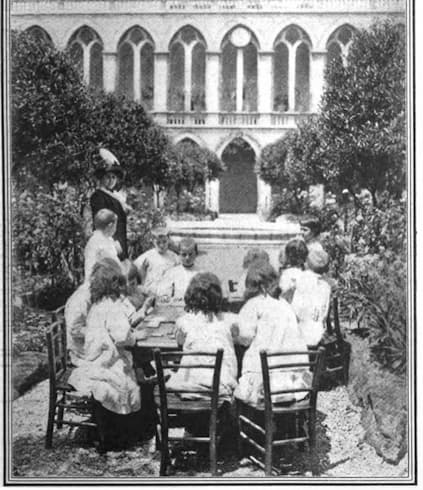

LITTLE GIRLS IN THE SCHOOL OF ST. ANGELO WELCOMING THE DOTTORESSA MONTESSORI, WHO HAS COME IN TO OBSERVE AND TO GIVE LESSONS

The Modern Baby No Longer the Play-

thing of its Parents

Madame Montessori starts all her system of primary training from the premise of independence and self-reliance which underlies the modern practice of infant hygiene –a comparatively new branch of medical science which, she says, has sprung out of the experimental methods of modern biology. A new-born baby is no longer allowed to be wrapped in folds of woolen or cotton cloth, to be shaken or patted into sleep, to be talked to and constantly handled. Its clothing is arranged to give its body as much freedom as possible. It is kept free from excitement,and is no longer made the plaything of its parents. The nurse has now become an observer rather than an arbitrary personage imposing her authority upon a helpless charge. The nurse's first duty is to watch the little animal grow; her second duty is to prevent the expenditure of energy by useless effort on the part of the child.

And these, Madame Montessori believes, are the first duties of the teachers of young children. The whole movement of society today is toward the protection of a child's individuality. Formerly, in hospitals, orphan asylums, and children's homes, the effort was to protect the child's life merely — to prevent infant mortality and to conserve somany living human organisms to society. But society is beginning to realize that it may have succeeded in preserving the living human organism and still have lost something that might have been infinitely valuable to the world. In other words, we have begun to give protection to the potential individual which is in every child's body – to keep it away from those things that would distort and destroy it, or force it into any given mold. We are trying to insure this individuality a chance to reveal itself, rare or commonplace, whatever it may be.

The protection of this individuality, then, is the foremost duty of the nurse in the first instance, and of the teacher in the second.

The most thoughtful modern teachers in America will find in the Montessori system all their best ideas reduced to scientific simplicity and precision. Dr. Montessori's chapter on discipline, one of the most important in her book, may be given briefly as follows:

Montessori Methods of Discipline

"Discipline through liberty. Here is a principle difficult for the followers of the common school methods to understand. How shall one attain discipline in a class of free children? Certainly, in our system, we have a different conception of what discipline is. If the discipline is founded upon liberty, it (the discipline) must be active. We do not call an individual disciplined only when he is rendered artificially silent as a mute and immovable as a paralytic. Such an individual is annihilated, not disciplined.

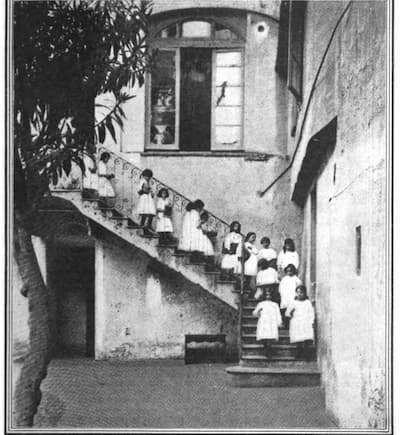

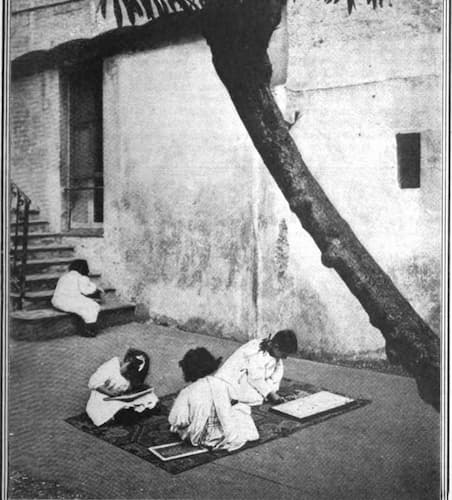

LITTLE GIRLS IN THE GHETTO SCHOOL OF ST. ANGELO, IN ROME, CARRYING THE MONTESSORI MATERIALS FROM THEIR SCHOOL-ROOM ON THE THIRD FLOOR TO THE OPEN COURT. THE CHILDREN MAKE THE JOURNEY DOWN THE STEEP FLIGHTS OF NARROW STEPS WITH PERFECT ORDER AND SECURITY OF MOVEMENT.

"We call an individual disciplined when he is master of himself, and can, therefore, regulate his own conduct when it shall be necessary to follow some rules of life.

"Such a concept of active discipline is not easy either to comprehend or to attain; but certainly it contains a great educational principle, and is very different from the absolute coercion to immobility.

"A special technique is necessary to the teacher if she is to lead the child along such a road of discipline, if she is to make it possible for him to continue in this way all his life, advancing always toward perfect self-mastery. Since the child now learns to move rather than to sit still, he prepares himself, not for the school, but for life; for he becomes able, through habit and through practice, to perform easily and correctly the simple acts of social or community life. The discipline to which the child habituates himself here is, in its character, not limited to the school environment, but extends to society.

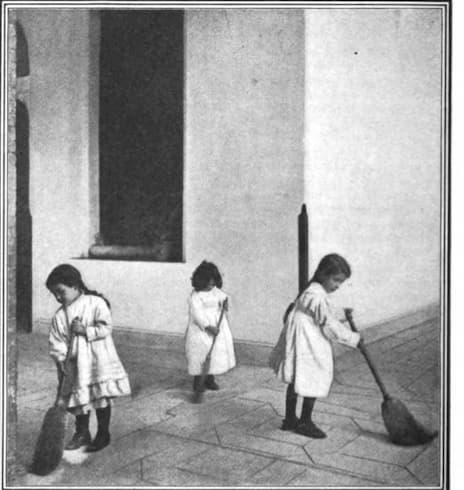

CLARA, FOUR AND A HALF YEARS OLD, PEPPINELLA, THREE AND A HALF, AND DORA, AGED FOUR, SWEEPING THE CORRIDOR. THE INDIVIDUALITY OF THE CHILDREN IS SHOWN TO SOME EXTENT IN THE PICTURE. CLARA IS SWEEPING VERY CAREFULLY. PEPPINELLA WITH GREAT VIGOR.

The Children Must Be Allowed to Perfect Freedom

"The liberty of the pupil must have as its limit the collective interests; as its form, that education of acts and manners universally considered good breeding. We must, then ,check in the child whatever offends or annoys others, or whatever tends toward coarse or ill-bred behavior. But all the rest — every manifestation having a useful scope, whatever it be and in whatever form expressed — must not only be permitted, but must be observed by the teacher. Here lies the essential point. From her preparation the teacher should bring not only the ability to observe natural phenomena, but an interest in doing so. She, in our system, must be a patiente (patient one), passive much more than active; and her patience shall be composed of anxious scientific curiosity, and of absolute respect toward the phenomenon that she wishes to observe. The teacher must understand and feel her position as an observer; the activity must lie in the phenomenon.

"Such principles surely have a place in schools for little children who are exhibiting the first spiritual and mental manifestations of their lives. We can not know the consequences of suffocating a spontaneous action when the child is just beginning to act; perhaps we suffocate life itself. We must respect religiously, reverently, these first indications of individuality; and, if any educational act is to be efficacious, it will be only that which tends to help toward the complete unfolding of the scope while the worlds whirl through space. This idea that life acts on itself, and that to study it, to divine its secrets, or to direct its activity, it is necessary to observe it, and to come to know it without intervening, is very difficult to grasp. The teacher has too thoroughly learned to be the one free activity of the school, for too long it has been virtually her duty to suffocate the activity of the pupils. If, in her first days in a Casa dei Bambini, she does not obtain order and silence, she looks about abashed, as if calling the bystanders to witness her innocence; in vain we repeat to her that the disorder of the first moment is necessary. When she is obliged to do nothing but watch, she asks if she had not better resign, since she is no longer a teacher. But when she begins to find it her duty to discern which acts of the child she ought to hinder and which she ought to observe, then the teacher of the old school feels a great lack in herself, andbegins to ask if she will not be quite inadequate to her task. In fact, she who is unprepared finds herself for a long time abashed or impotent, inner life of the child. To be thus helpful, it is necessary rigorously to avoid the arrest of spontaneous movements and the imposition of purely arbitrary tasks. It is, of course, understood that here we do not refer to use less or dangerous actions, for these must be suffocated –destroyed.

The Old-Fashioned Teacher Suffocated the Activity of Her Pupils

"The training of teachers not prepared for scientific observation, or perhaps trained in the old imperialistic methods of the public schools have convinced me of the great distance between those methods and this. Even an intelligent teacher who understands the principle finds much difficulty in putting it into practice. She can not understand that her task is apparently passive, like that of the astronomer who sits immovable before the tele while the broader the scientific culture and the practice in experimentation of a teacher, the sooner will come for her the marvel of unfolding life and her interest in it.

"In those first days of training my teachers, I saw the dangers of blind intervention in the children's activities. These teachers almost involuntarily recalled the children to im mobility, without observing and distinguishing the nature of the movements that they repressed. There was, for example, a little girl who gathered her companions about her, and then, in the midst of them, began to talk and gesticulate. The teacher at once ran to her, took hold of her arms, and told. her to be still; but I, observing the child, saw that she was playing at being teacher or mother to the others, and was teaching them the morning prayer, the invocation to the saints, and the sign of the cross; she already showed herself as a director. Another child, who continually made disorganized and misdirected movements, and who was considered abnormal, one day, with an expression of intense attention, set about moving the tables. Instantly they were upon him to make him stand still because he made too much noise. Yet this was one of the first manifestations, in this child, of movements that were coordinated and directed toward a useful end, and it was therefore an action that should have been respected. In fact, after this the child began to be quiet and happy like the others whenever he had any small objects to move about and to arrange upon his desk.

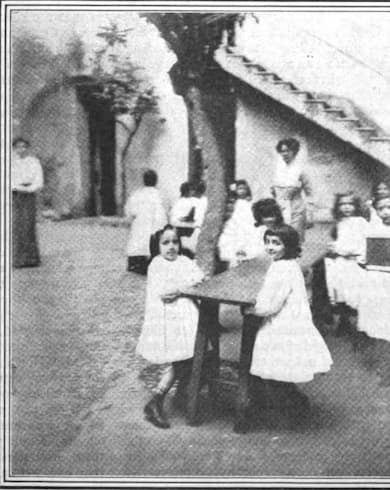

LITTLE GIRLS ARRANGING THEIR WORK-TABLES IN THE COURTYARD OF ST. ANGELO IN PESCHERIA

The Ordinary Teacher’s Mistaken Notions of Helpfulness

"It often happened that, while the directress replaced in the boxes various materials that had been used, a child would draw near, picking up the objects, with the evident desire of imitating the teacher. The first impulse was to send the child back to her place with the remark, 'Let it alone; go to your seat.' Yet the child expressed by this act a desire to be useful."

Madame Montessori here gives an illustration of a little girl of two and a half who, finding that she could not see either under the legs or over the heads of the other children, who were crowded about a basin of floating toys, stood for a moment in deep thought; then, with her face alight with interest, ran toward a little chair, with the evident intention of placing it so that she might see over the heads of her friends. Just at this moment she was spied by a young teacher, who, before Montessori could prevent, seized the baby and, lifting her up so that she could see above the heads of the others, cried: "Come, dear, come, poor little one, you shall see, too." Montessori says:

"Certainly the child, seeing the toys, experienced no such joy as that she felt in overcoming the obstacle with her own powers. The teacher prevented the child from educating itself by bringing to it any compensating good. She had been about to feel herself a victor, and instead she found herself held fast in two imprisoning arms, an impotent.

Goodness Too Often Confounded with Immobility

"When the teachers were weary of my observations, they began to allow the children to do whatever they pleased. I saw children with their feet on the tables, or with their fingers in their noses, and no intervention was made to correct them. I saw others push their companions, and I saw dawn in the faces of these expressions of violence; and not the slightest attention on the part of the teacher. Then I had to intervene to show with what absolute rigor it is necessary to hinder, and little by little suffocate, all those things which we must not do, so that the child may come to discern clearly between good and evil. The first idea that the child must acquire, in order to be actively disciplined, is that of the difference between good and evil; and the task of the educator lies in seeing that the child does not confound good with immobility, and evil with activity, as often happens in the case of the old-time discipline. And all this because our aim is to discipline for activity, for work, for good; not for immobility, not for passivity, not for obedience.

"A room in which all the children move about usefully, intelligently, and voluntarily, without committing any rough or rude act, would seem to me a class-room disciplined very well indeed.

"To seat the children in rows, as in the common schools, to assign to each little one a place, and to propose that they shall sit thus quietly observant of the order of the whole class as an assemblage — this can be attained later, the starting-place of collective education. For also, in life, it sometimes happens that we must all remain seated and quiet, when, for example, we attend a concert or a lecture. And we know that even to us, as grown people, this costs no little sacrifice.

"If we can,when we begin this collective education, arrange the children, sending each one to his own place in order, trying to make them understand the idea that, thus placed, they lookwell, and that it is a good thing to be thus placed in order, that it is a good and pleas in arrangement in the room, this ordered and tranquil adjustment of theirs — then their remaining in their places, quiet and silent, is the result of a species of lesson, not an imposition. To make them understand the idea of the practice, to have them assimilate a principle of collective order — that is the important thing.

"If, after they have understood this idea, they rise, speak, change to another place, they no longer do this without knowing and without thinking, but they do it because they wish to rise, to speak, etc.; that is, from that state of repose and order well understood they depart in order to undertake some voluntary action; and, knowing that there are actions which are prohibited, this idea of collective order will give them a new impulse to remember to discriminate between good and evil.

"The movements of the children from the state of order always become more coordinated and perfect with the passing of the days; in fact, they learn to reflect upon their own acts. Now, with the idea of order understood by the children, the observation of the way in which they pass from the first disordered movements to those which are spontaneous and ordered— this is the book of the teacher; this is the book which must inspire her actions; it is the one in which she must read and study, if she is to become a real educator."

How Awkwardness is Done Away Within the Casa dei Bambini

Sense training is one of the most important factors in obtaining this discipline through liberty. The children in Casa dei Bambini are just at the age when they are forming all their bodily habits. If these are properly fixed in the beginning, that awkwardness and clumsiness which are the chief incentives to uncouth behavior are practically done away with by the time the child is out of infancy. Everything that he handles and works with in the Casa dei Bambini has been carefully planned for his use. The squares of carpet upon which the children work are so small that they can conveniently brush and fold them and carry them about. The tables are so light that babies of two and three can easily move them. When the children are taught to wash their faces and hands, they use little basins and pitchers which they can handle easily and safely. The cup boards in which the children keep the apparatus are low and open easily. The children are provided with three kinds of comfortable chairs, although they spend a good deal of their time standing by the tables or sitting on the squares of carpet. By the time the children are five or six years old, therefore, they have a repose and freedom of body that make them masters of themselves. Not only the sense exercises, but every piece of apparatus used, as well as the furnishing of the school-room, is the result of an investigation as scientific and thorough as it is human. Every piece of apparatus or furniture has been tested by use in many schools, and by a large number of children. Nothing in the Casa dei Bambini is accidental; the apparatus and the appointments of the schools represent twelve years of study and experimentation on Dr. Montessori's part. Indeed, Montessori says that her method of teaching represents the work of three physicians, Itard, Seguin, and herself, and that it began at the time of the French Revolution.

The Disturbing voice of the Teacher

Rarely Heard in the Montessori Schools

The gulf between the cultivated mentality of the adult and the primitive groping mind of the most precocious child is so great that even gifted children unconsciously tax their brains in the effort to understand and to assimilate the words that most teachers use in presenting a lesson or directing a game. Dr. Montessori sternly discountenanced tenancies the folly of useless words. She insists upon the direct presentation of the object in the simplest manner, with the fewest words possible.

In the Casa dei Bambini, the teacher, when she is preparing to give a lesson, seats herself beside the little one and firmly and distinctly calls his name. To sit down beside a little child in the attitude of a comrade, and to call his name distinctly, clearly, is to call, not to the body, but to the master spirit and owner of that body. Hearing his name, the child instantly knows that something is required of him. When, by his expression or byan intelligent gesture, he responds to this personal call, the teacher may begin herlesson, saying calmly, intently: "Listen!" No other explanatory word.

Giving a Lesson on Color

In her lesson on color, which is one of the first lessons that Montessori gives to children of three and a half or four, the teacher selects from the boxes of flat spools wound with colored silks two or three colors strongly contrasted and in pairs. The lesson proceeds according to the three periods borrowed by Montessori from Seguin. Let us suppose the colors chosen to be red and yellow.

"Yellow," says the teacher, putting down the first spool of that color.

The average child will at once look pleased with the brilliant object. "This is yellow," the teacher may say again. She must repeat the name of the color clearly and emphatically, that the sound may carry a meaning.

After a moment's pause, when she is quite sure that the child's eye has absorbed the yellow color, she puts down the second color, saying, "And this is red — red — red." The child commonly is moved to take the object in her hands and look at it. She has seen both of these colors before, many times, probably has been attracted to them before she could speak or even crawl; for all babies with normal sight usually laugh and crow at the sight of bright colors.

Notwithstanding the fact that the teacher knows that the child likes and recognizes yellow and red, she must allow her to contemplate the bright pieces for a moment undisturbed. A large proportion of children know the colors only perfunctorily, and in this lesson will come the first intellectual idea in connection with them. They will look at yellow or red for the first time in an intelligent fashion. For this reason the child must not be hurried. Some children absorb ideas slowly, and this is a very new, large, and important idea for the little brain. When she requires more information, she will look up with an intelligent glance.

Then only may the teacher proceed to the second period, which is to prove whether the child has understood the contrast and the names of the two colors. It is the trial of precision.

"Give me the yellow," demands the teacher. Then, "Give me the red." If the child obeys correctly and properly,– which is almost invariably the case with strong colors, unless the vision is defective, then comes the third period of the lesson. The teacher points to the yellow object and says: "What color is that?" And then, being answered accurately, the three periods are closed.

Then may follow the little game in which, by the use of duplicate stimuli, Dr. Montessori so often allows the child to establish for himself the points in the explanatory lesson. Taking the two red spools, she places them carefully side by side, saying: "See, these are the same; these are red." Then, having done the same with the blue and yellow spools, she breaks up the neat little carpet of colors and, mixing the spools, says, pointing to the red piece: "Give me the one like this." When the child has done this, she lets him place the two side by side, as she did, and leads him to pair, in this way, the other colors. She then shows him how to break up the line he has made, and leaves him to play the game by himself.

The Individual Taste of Each Child Must be Respected

If the child fails to respond to one of these periods, the teacher must not urge her. The little one has not learned the colors, either because her eyes are defective, or she was not sufficiently interested at the moment, or perhaps her young intelligence was not yet ripened to care about the matter at all. In such a case, the teacher, with a smile or a caress which implies that the child is not to continue trying to do a thing that seems wearisome to her, will leave the little one at liberty to go and get some game she knows and which pleases her more. Dr. Montessori says in her book: "If a child fails to respond at once to the lesson, the teacher must leave her, in order that the brain shall remain quite clear to receive a new impression the next time this lesson is attempted." If a child does not respond voluntarily to the object, nothing that the teacher can say is likely to help him much. When a child touches an object which appeals to his intelligent curiosity, he receives an infinitely greater stimulus than he can possibly receive from words. There are certain minds that spring forward to comprehend, and which in turn react, almost before they are called; others need to be led slowly, gently, before the same result is attained.

It is impossible to change fundamental qualities of mind. Not all children will respond to these exercises in the same way. Some children are anxious to drop an object as soon as they grasp its meaning; others never appear to take actual pleasure in it until they realize the scope of the object, and then love to repeat the exercise with it countless times. Dr. Montessori never ceases to reiterate that the tastes of each class of mind must be respected, encouraged, and strictly observed. Her teachers must never for one moment forget that "lilies can never be transformed into roses, nor can any amount of training change the personality or alter the color of the soul."

Dr. Montessori has the great sympathetic soul which is the basis of her physician's temperament, and it was in caring for unfortunate children that her genius discovered a method to broaden the outlook, lighten the drudgery, and assist the tender brain of the normal child. Her great and brilliantly emphasized principle is that, from the first entrance into the garden of education, the dignity of the individual explorers must be respected. He may be led to look upon the character of the flowers and plants, and to be guided into the best and most useful paths, but he must be left to choose the plants which he wishes to examine, to understand, and to cultivate.

She does all she can in training her teachers to understand this theory; she reiterates,she repeats, she emphasizes, she reproves; she goes personally into the classes to show her teachers how to handle the children, so that their nerves may be kept calm and their brains left untaxed. The only Casa dei Bambini as yet established by the Roman board of education has so many interesting circumstances in connection with its foundation, developments, and ultimate results, that I have selected it to illustrate this article.

The School of St. Angelo in the Roman Slums

A STREET IN THE GHETTO OF ROME. IT IS FROM THIS FILTHY, DISEASE-STRICKEN QUARTER THAT THE CHILDREN OF THE ST. ANGELO SCHOOL COME.

This school is situated in the picturesque and foul quarter of the mediaeval Ghetto. The dark, reeking streets and lanes, which wind about and lose themselves near the AraCoeli, skirting the old palace of the turbulent Orsini, swarm with a population diseased,filthy, and degenerate. In this appalling setting the Signora Galli Saccenti, principal of a girls' public school, actually persuaded the Roman board of education to organize a Casa dei Bambini. Her first endeavors met everywhere with stolid indifference and intense opposition. The poor parents of that squalid region have no political influence; nor, indeed, have they vigor enough in their miserable frames to do anything more than turn the children they bear (their “creatures,” to use the pathetic Italian term) into the narrow, noisy, dirty streets. This region was in the olden times the haunt of the pest,and to-day is a breeding place for every epidemic. The physicians fear it, and the authorities have little interest in it or in its denizens. At first the municipal officials hardly listened to Signora Galli's eloquent appeals; but finally she compelled attention,and at last she was permitted to use a bare, desolate room in the school of which she is superintendent. This room and a narrow courtyard, with the promise of the didactic materials necessary to teach the method, was all she could get from the Roman bureau of education. With eagerness, if not with thankfulness, Signora Galli took what they would allow her. To overcome the squalor, and to inspire the pupils, she brought the riches of her own glorious spirit.

There are none of the comfortable chairs suited to little bodies, or the light, well-balanced low tables seen in the other Case dei Bambini. The board would not expendone penny beyond buying the didactic materials. In the class-room were the usual impossible Italian school benches and narrow, cramped desks. The cupboards for the didactic materials were devised by the ingenious Signora Galli long before there was any material to put into them. The top sections from two of her office bookcases were placed flat on the floor, forming cupboards in which the children might keep the precious materials in order.

Last October, when the schools of Rome opened, Signora Galli had done all she could to put the bare, ugly room in readiness; but she discovered that the dilatory Roman school board had not yet ordered the didactic materials from Milan. Nothing daunted, Signora Galli began to work without them. Dr. Montessori was especially interested in this school because of the predicament in which Signora Galli found herself, and she devised a program which gave the children the same sort of training that the use of the apparatus gives them.

The children were taught (as much as possible in the open courtyard and through the medium of entertaining games) how to move gracefully and carefully, and how to bring their muscles into coordination. The little ones were encouraged to be free and spontaneous in all happy, useful activities, and to avoid ugly or harmful behavior.

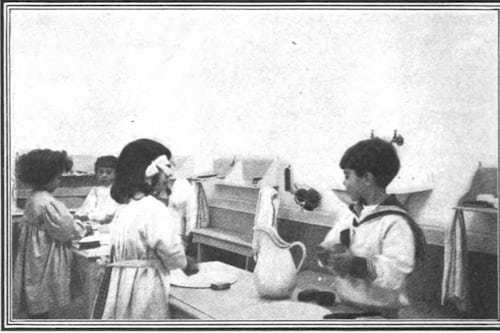

CHILDREN AT WORK IN THE ST. ANGELO SCHOOL IN ROME. THE LITTLE GIRL ON THE CARPET WHO IS COMPOSING WITH THE CUT-OUT PAPER LETTERS HAS BEGUN A SENTENCE TELLING THAT "FORESTIERI" (STRANGERS) FROM ANOTHER COUNTRY HAVE COME TO VISIT THE SCHOOL.

Children of Three and Four Learn to Bathe and Dress Themselves

The children were taught how to wash the different parts of their body, their faces, their hands, their necks and ears, their feet, and even to take a complete basin bath. Although the little girls in the school came from the most miserable home conditions imaginable, there were so imbued with the spirit of the teaching they received there that, although they had no basin and no room to bathe in, they took their Sponge bath at the edge of the fountain in the neighboring public square, Signora Galli herself having given them soap.

All the little girls were taught to brush and comb one another's hair, and to dress and undress themselves in an orderly and intelligent fashion. They were taught to move safely and quietly in the cramped spaces between the desks and chairs, to carry about breakable objects of various shapes securely, to place them in order upon the desks and to put them back was every evidence, from their appearance and from the reports of their mothers, that they actually took a basin bath every morning before coming to school. Two little girls who attended the school were so poor that they were without a home at all. Their mother was a laboring woman who was able to earn so little that she and the children had no shelter all winter except the portone (entrance-hall) of a miserable tenement-house. In this bare vestibule the little girls slept, with their mother, on a straw pallet, and here they kept the brazier and the single cooking-pan for macaroni which constituted their entire household goods. But these little girls, who spent every day in the kindly atmosphere of the Casa dei Bambini, again into the cupboards. They were taught to open and close doors quietly, to make the room tidy, and to walk with secure confidence up and down long flights of steps leading to the courtyard.

The defects of speech so common in the classes from which these children come were corrected, in a measure, by the light gymnastics of the lips and throat used in all the Montessori schools. The informal conversation which is part of the curriculum in the Case dei Bambini furnished an opportunity for helping them to articulate common words distinctly and to express themselves clearly. By the time the materials arrived, a happy discipline was completely established in the school.

An American Teacher’s Impression of a Montessori School-room

"There was no formal morning opening of school, and it was a surprise to me, while I stood talking with the teacher in the empty classroom, to turn suddenly and find a group of little girls in clean aprons behind me. They had come in quietly, and were waiting to wish me good morning. These were children from the Ghetto, but, aside from the pallor that arises from inadequate nourishment, the faces before me had nothing in common with those of the poverty-stricken inhabitants of the streets along which I had picked my way. The happiness, the intelligence, and the ease with which the children welcomed me showed that some better force was at work within these natures. And, as I watched, my wonder grew. With a directness and simplicity which showed that she knew what she wanted and how to get it, each little girl took from the cupboard or from her miser able little desk the materials with which she wished to work. In this class of forty-five children I saw not one idler. Two little girls brought from its corner a square of carpet, old, cheap, and shabby, but absolutely clean, and this they spread in a narrow space in front of one of the desks; then, bringing a box containing the cut-out letters, began with joyous eagerness to form these letters into words and phrases. One of these phrases, made seriously enough, interested and amused me. The child composing this sentence pronounced each word sotto voce as she selected the letters from the box, and then put them carefully in their place in the words she was forming on the old carpet. The sentence was as follows: ‘Teresina does not like to bathe, but her little dog gladly goes into the fountain." Signora Galli found, upon in quiry, that this spontaneous bit of composition had been inspired by an encounter the composer had that morning had with the unregenerate Teresina and her dog.

"The children in the Montessori class of this public school take great pride in their clean bodies, and have learned to respect themselves and their class-room too much ever to come into the school unwashed. They wipe their feet so carefully, before coming into the hallway, that the janitor, unaccustomed to such habits, is in a constant state of marvel. If, in their homes, the mother fails to have ready the clean apron which she is expected to furnish, her child protests and shows such a true distress that the repetition of such carelessness on the part of the mother is very rare.

CHILDREN OF THE ITALIAN NOBILITY, AT THE MONTESSORI SCHOOL ON THE PINCIAN HILL, WASHING THEIR HANDS. THE CHILDREN USE LITTLE PITCHERS AND BASINS WHICH THEY CAN HANDLE EASILY, AND LEARN TO FILL THE PITCHERS AT THE FAUCET, POUR THE WATER, AND WAIT UPON THEMSELVES WITHOUT HELP

What Children Six Years Old Have Accomplished

"I saw other children composing words with these same cut-out letters, and placing them with the greatest solicitude on the slanting planes of the narrow desk-tops, so that they might not slip to the floor. Others were writing on the blackboard, and some had slates on which they were drawing letters in chalk. Some were sitting on the benches,some on the floor, and some on the few comfortable little chairs that Signora Galli had placed, at her own expense, in some of the corners of the crowded little room. With all this activity there was no noise or disorder. Instead, there was joy in work and a happy comparison of tasks. Occasionally, as I stood watching, a child would come to call Signora Galli to see some word that she considered particularly well written, or to beg her to pronounce slowly and distinctly some other word that she wished to write. In the attitude of the children toward their teacher and their directress I observed the most beautiful reverence, the warmest affection, and the greatest respect.

"The thing that struck me the most forcibly was the event, or, to speak in school parlance, the perfectly graded condition of the entire class. The greater number of these children were six years old when they entered in the fall, and they had, through the preparation which was done through the month of waiting, established their ideas about sense education. So it seemed, at the time they received the materials, we might consider that the children in this school presented somewhat the same problem we might face in offering these toys to one of the first graders in America. They accepted the simpler exercises easily, and spent much less time in mastering them than the younger children. Over the games with the geometrical figures and insets, through which the sense of form is trained, these children spent a much longer time; and the exercise of filling in the spaces drawn by the conventional shapes, which directly precedes the act of writing, which was continued by many of them throughout the year.

"So much for the progress of this school, as measured by ordinary public-school standards. But of the life, the joy, the individual independence which I saw in the children themselves and in everything they did, and which made their work valuable, I can give no adequate description. To sit for an hour in the little brick-paved court with its narrow strip of garden and two eucalyptus trees, and to watch the children at work, was to feel that, during the year spent there, these little waifs of the Ghetto had found that personal liberty and self control that alone make it possible for any human being to do his best work and to adapt himself to the conditions of the life about him.

Holding School Out of Doors

"One morning, sitting among the children in their school-room, I heard Signora Galli's assistant say quietly: ‘Let's have school in the court now.' That was all she said. Yet I have seen many teachers fail, with a dozen explicit commands, to achieve the result that I witnessed after this simple sentence. The effect was immediate. There was no scrambling, no confusion. Quietly, tranquilly, and with the security that results from knowing how to do things, forty-five little girls put themselves to work getting ready to go down into the court. Each one supplied herself with what she would need for her work. Three children who at the time were composing sentences on the little carpet placed all the letters carefully in the large flat box made to receive them, and then one of them put on the cover and held it carefully, while the other two brushed the strip of carpet and rolled it into a bundle which they could carry downstairs between them. Several other children, who were using pen and ink for the first time, dried their freshly written lines, wiped their pens, and, holding the ink wells with the greatest care, made ready to follow their companions. There were others who furnished themselves with chalk, slates, boxes of letters, counters and rods for the number work, and cases of metal geometric forms with colored pencils for filling in the designs. There was no pushing nor disorder, though much happy talk and laughter. When all was ready, the teacher did not give a command for silence; she only smiled and moved toward the door; then, quite naturally and in perfect order, the children followed her. There was a hall to cross, two doors to open, and three flights of narrow, awkward stone stairs to descend. I, who have taken classes up and down stairs for many years, could only feel, when I saw the security and patience displayed in the movements of these children, that the sense-training exercises had given them a control that I had never attained with children and have seldom seen in grown people. At the second flight of stairs we came upon the janitor, who was sweeping down the steps with wet sawdust. The line halted voluntarily while he brushed a tiny path clear, and then, with evident pleasure, each child daintily picked her way through this cleared space.

The Montessort Method Popular with the School Janitor

"Giuseppe, the janitor, is very fond of the children in this class. He told Signora Galli an incident that gives a good example of the social and spiritual effect of such an education. It so happened that he one day brought his ladder and bucket into the school-room while the children were at work, and washed the windows and ventilators.The children watched him with friendly interest; and when he had finished, and was about to depart with his buckets, several of them, gazing admiringly at the shining glass, said to him: 'Graçie tante, Giuseppe; ha fatto molto bene.' ('Thank you so much, Giuseppe; you did that wonderfully well.') The old man's astonishment and pleasure were extreme; and when one considers that these children come from homes where rudeness and scolding voices are accepted things, it is easy to understand his surprise.

In teaching these children of St. Angelo in Pescheria, neither reading nor writing nor the use of the materials were the main aim or desire of Signora Galli and her assistant. Had these inferior ambitions been allowed to influence the work in the school, there would have been little accomplished in the long months of waiting for the didactic toys, months that proved so valuable in the real education of these poor children.

Although nearly all the pupils in the class just described were six years old, the system is much more effective, of course, when the sense training is begun with children of three or three and a half, and followed slowly and thoroughly. The children from the Ghetto were less developed than children born into more fortunate conditions, and their sense habits were less fixed. The great value of early training by the Montessori method is illustrated by the following case.

A Private Governess' Experiene in

Applying the Montessori Method

A private governess who has two little girls in charge, one seven and the other nearly five, gave me a most interesting account of the difference in effect of an early and late application of the method. The governess took charge of these children three and a half years ago. Up to that time the elder girl had been taught in the ordinary way. She had never been trained in the light gymnastics especially devised to give children a mastery over their legs and arms; nor had she had the sense-training exercises which do so much to give a child self-mastery and poise. Under the supervision of the governess, the younger girl, on the contrary, was trained entirely by the Montessori method. These two children for the past three years have been following the same path of education. In reading and writing the elder one is naturally much in advance of the younger; but she lacks the repose, the coordination of muscles, and the happy tranquillity in play and work which at once attract older people to the younger. They are the children of rich parents, who live in a large country house with a score of servants at command; but, while the younger delights to carry upstairs to her mother a bowl of flowers, and can do so with out spilling a drop of water from the well-filled receptacle, the elder girl can not possibly pass a small plate of cakes around the tea-table without tilting it so that some of the cakes slip onto the floor. Yet the elder child has fingers strengthened by judicious piano lessons; the younger children's hands have been trained by the tactile exercises and the practical every-day work done in the Montessori schools. The same contrast is exhibited between the two sisters in the way they perform every-day duties, such as tying their shoes, taking care of the bird-cage, watering the flowers, etc.

Queen Margherita and the School Child

QUEEN MARGHERITA VISITING A MONTESSORI CLASS IN THE SCHOOL OF ST. ANGELO.

THE QUEEN HAS TAKEN A GREAT INTEREST IN MONTESSORI'S WORK

The habits of order, the interest, and the sense of the importance of the work in hand, which is always found in the Montessori classes, is illustrated here by the following circumstance. On a day of great excitement, when Queen Margherita visited one of the schools, she asked a little girl, who was engaged in putting in order a box of cut-out letters, to spell some words for her. The child made no reply, but went on calmly dropping each letter into its own compartment. An older person, standing near, horrified at the child's indifference, exclaimed:

"But, Rosa, you must pay attention! This is the Queen!"

"I know that," the child answered respectfully. "But the Queen knows that, before I begin to spell, I must first finish my work of putting the alphabet in order."

In the classrooms of the various Montessori schools in Rome, the fact that the disturbing voice of a teacher is little heard induces a spirit of repose which all the children unconsciously feel. Often the teacher writes on the blackboard instructions for the pupils to leave their work and go into the courtyard or garden, to play or sing. The older children read the sentence, and the younger ones, who have not yet learned to read, follow when they see the others arise and depart.

During the past winter, professors from the foremost colleges in the United States, principals of schools, and many other interested persons have visited the Casa dei Bambini in Rome, and have seen substantial proofs that encouragement of perfect liberty does not imperil discipline among young and nervously organized human beings, if their dignity and proper independence is respected and they are led to respect themselves.

Last year a group of Italian noblewomen established the Pincian Hill school for their own children and the children of the various embassies. The Montessori plan has been as brilliantly successful there as among the children of the poor.

The problem presented was a difficult one, made so by the varying nationalities and the differing home influences. Confusion reigned at first; but, before a month had passed,the simple sense exercises, the respect shown by the teacher toward good and happy acts and her frank correction of selfish ones, had converted this Tower of Babel into a community of happy, busy children.

Still young and full of enthusiasm, Dr. Montessori has by no means completed her work. Far-seeing Italians, appreciating what she has done for Italian children, believe it imperative that she have a school of her own, where she will be able to give her teacher a more thorough training, and where, retaining from year to year the same group of children, she will be able to apply to the work of the higher grades her ideals of discipline through liberty.

In her January article Miss Tozier will describe in detail the Montessori educational apparatus, and will show what is accomplished with each toy. Arrangements have been completed for the manufacture and sale of this apparatus by the House of Childhood, 606 Flatiron Building, New York City, under the management of Mr. Carl Byoir. The manufacturers of the apparatus hope to place the material within the reach of parents and educators by the first of January.

Dr. Montessori's representative in this country will collaborate in the preparation of a book of instructions and suggestions which will be sold with each set of the apparatus.

Matt Bronsil is the author of these posts. He can be contacted at MattBronsilMontessori@gmail.com

<<< Back to the McClure article list <<<

Recommended McClure/Montessori Books

Montessori History Blogs

History of Montessori

Maria Montessori

History of Montessori in Taiwan

History

Mario Montessori

Mario Montessori

McClure's Magazine

McClure's Magazine

Montessori Video

Teachers TV: The Montessori Method

Read Old Magazine Articles

Old Montessori Articles

EFL and Montessori

EFL and Montessori