The following article was printed in McCLURE'S MAGAZINE

VOL. XXXVII --

MAY, 1911 --

No. 1

AN EDUCATIONAL WONDER-WORKER

THE METHODS OF MARIA MONTESSORI

Note: I am including all the images and captions from the original article, but not in their original place. I tried to place them in places that made better sense in the context of the article.

Sections and Links:

The Wild Boy of Averyon

Maria Montessori's Work in the "Mind-Straightening School"

Rome Deals with Her Tenement Problem

The "Houses of Childhood"

Maria Montessori Rediscovers the Ten Fingers

Learning the Difference Between "Rough" and "Smooth"

Children Correct Their Own Mistakes

No Naughty Children in the "Houses of Childhood"

Children of Three Learn to Tie Bow Knots and to Fasten Buttons and Clasps

Recognizing a Circle or a Square by the Way it Feels

Maria Montessori's Pupils Able to Distinguish Blindfold between a Grain of Millet and a Grain of Rice

The "Game of Silence"

Teach Their Children To Write

Making Words with Cardboard Letters

Maria Montessori's Pupils Begin to Write

Frenzy of Writing Takes Possession of the School

Children of Four Learn to Write in Six Weeks

The Game of Learning to Read

Related Links

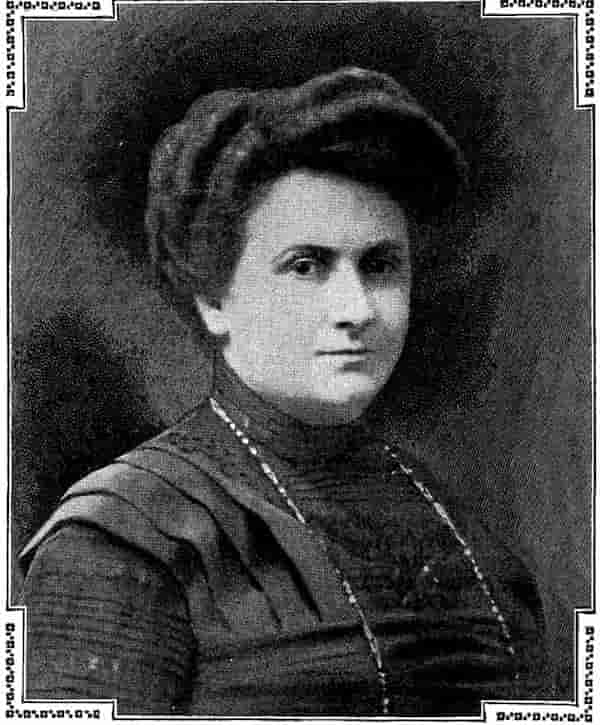

MARIA MONTESSORI

THE ITALIAN EDUCATION WHO HAS ORIGINATED A NEW AND REMARKABLY SUCCESSFUL METHOD OF TEACHING YOUNG CHILDREN

The story of the Babes in the Wood has sometimes been reenacted in real life, and the robins have not always had to play the part of sexton an cover the little bodies with leaves. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, about ten "wild" boys and girls were discovered in various parts of Europe, who, having been exposed in desert places, had contrived to live for many years the life of the other animals around them. The most famous of these Orsons was known as the Savage of Aveyron. His case was much discussed in the opening years of the last century; and attention has recently been redirected to it by the fact that it formed the starting-point of a process of thought and experiment that bids fair to revolutionize primary education, by practically abolishing the difficulty of learning to read and write.

The Wild Boy of Aveyron

In a forest of the Department of Aveyron, France, some hunters, in 1798, caught a wild boy, apparently eleven or twelve years of age. His body was covered with scars, caused by briars, thorns, and the teeth of animals; but one scar on his throat seemed to show that whoever left him in the forest had first tried to murder him. He was eventually brought to Paris and placed under the care of Dr. Itard, physician to the National Institution for the Deaf and Dumb. Itard lavished infinite patience and ingenuity upon his education, but with very little effect, for the boy proved to be an idiot. Though he was not deaf, he never even learned to speak; and, when he died in 1828, his intelligence was still inferior to that of many animals. Nevertheless, the effort to educate him had not been wasted, for it had educated Itard, who had arrived at many valuable conclusions as to the best methods of dealing with cases of unawakened or defective intelligence.

These conclusions he handed on to his pupil Edouard Seguin, but helped him still more, perhaps, by inspiring him with an enthusiastic and indefatigable interest in the subject. Seguin (born in 1812) soon became a noted specialist in the treatment of defective children, and, in 1839, opened the first school for idiots in France. In 1850 antagonism to the ambitions of Louis Napoleon (then Prince-President) led him to emigrate to America. After spending some years in Cleveland and in Portsmouth, Ohio, he removed, early in the 1860's, to New York City, where he remained until his death in 1880. He was greatly esteemed by the leading physicians of his adopted country, and exercised a determining influence on the training of defective children in America. Not one idiot in a thousand, he declared, was entirely refractory to his treatment; not one in a hundred but was rendered more happy and healthy. "More than thirty per cent have been made capable of working like one third of a man; more than forty per cent of working like two thirds of a man; while twenty-five per cent came nearer and nearer to standards of manhood."

Maria Montessori's Work in the "Mind-Straightening School"

Seguin had published in Paris, in 1846, a book called Traitment moral, hygiene et education des idiots; and this, one day, fell into the hands of Maria Montessori, the first woman ever granted the degree of Doctor of Medicine by the University of Rome. As Assistant Doctor in the Clinic of Psychiatry, this lady was already interested in the care of the mentally deficient. Seguin's exposition of his method of "pedagogic cure" fell in with her own line of thought, giving precision and certainty to ideas already germinating in her mind; and Seguin led her back to the "admirable experiments" of Itard. At the Pedagogic Congress at Turin, in 1898, she so ably expounded her views that the Minister of Public Instruction, Signor Baccelli, invited her to give a course of lectures in Rome to teachers interested in the treatment of backward children. This course of lectures led to the foundation of the Scuola Ortofrenica, or "mind-straightening school," attended by feeble-minded children from all the asylums in Rome, as well as by private pupils sent thither by their parents. For more than two years Maria Montessori was the directress of the institution.

The results she attained were considered miraculous. Idiots sent to her from the public asylum she taught to read and write so that they could pass the same examinations that normal children of their age were expected to pass at the public schools. How was this surprising success achieved? The secret, she says, was simple:

It was that the boys from the asylum had followed a different path from that pursued in the public schools. They had been aided in their psychic development, while the normal children had been hampered and depressed. I thought that if, one day, the special education which had thus marvelously developed the idiots could be applied to the development of normal children, the miracle would vanish, and the gulf between the inferior and the normal mentality would reappear, never again to be bridged. While every one was admiring the progress of my idiots, I was meditating on the reasons that could keep the happy and healthy common-school children on so low a level that my unhappy pupils were able to stand beside them.

When, in 1900, she left the Scuola Ortofrenica, Maria Montessori reentered the University of Rome as a student of philosophy. She devoted herself, in particular, to experimental psychology, then a new study in the Italian universities; and, at the same time, she visited and inspected all the primary schools within her reach, carrying out researches in pedagogic anthropology, and studying the methods and arrangements currently employed in the education of normal children.

After seven years of indefatigable study in every branch of experimental pedagogy, the opportunity for putting her principles into practice came to her in a manner as ideal as it was unexpected. In 1906 she came in touch with a well-known engineer, Edoardo Talamo, who offered her the entire charge of some new infant schools about to be established in Rome. No fairy godmother could have provided her with an opening more exactly to her mind.

Rome Deals with Her Tenement Problem

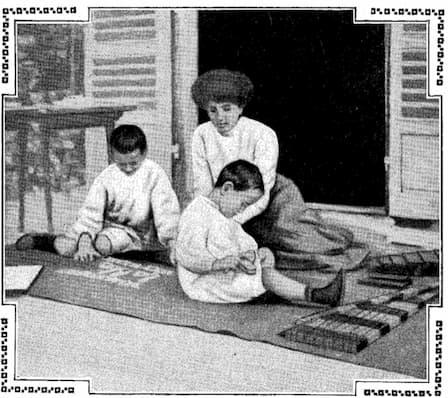

THE MARCHESA RANIERI DI SORBELLO, AN AMERICAN WOMAN, WITH HER TWO SONS, WHO HAVE BEEN TRAINED BY THE MONTESSORI METHOD. THE YOUNGER BOY, WHO IS ONLY THREE AND A HALF, CAN READ AND WRITE IN BOTH ENGLISH AND ITALIAN.

For these were not ordinary infant schools. they were part of a great endeavor for social betterment. Toward the end of the 1880's there had been an extravagant building "boom" in Rome, which had been duly followed by the inevitable crash. While the mania was at its height, a whole new quarter of apartment houses had been run up outside the Porta San Lorenzo, where the tramways start for Tivoli.

The crash came before they had ever been occupied, and they found no tenants of the class for whom they had been designed. But they found poor tenants in plenty. An astute slum speculator would rent a flat of six or seven large rooms for $8 a month, and would sublet it, room by room, even down to the corridors, at rates that brought him in $16 a month, while he himself lived at free quarters, and probably eked out his gains by petty usury among his tenants.

Thus the district became one of the most crowded, insanitary, and vicious "warrens of the poor," in which children grew up without light, without air, in precocious familiarity with every form of crime and degradation. The evil became so crying that an association was formed to attempt its remedy. This was the Institute Romano di Beni Stabili — the Real Estate Institute of Rome. It acquired a great part of the quarter of San Lorenzo, where it possesses fifty-eight houses, containing no fewer than sixteen hundred flats. Its first care was to transform the great blocks into sanitary dwellings, thoroughly adapted to the uses of poor tenants. It pulled down all central structures that shut out light and air, and thus created a spacious courtyard in the middle of each block. It redistributed the apartments, so that several families no longer inhabited one large flat, but each family had a little flat of its own. It erected new staircases, to prevent crowding. In short, it transformed very ill-adapted into very well-adapted dwellings, and it offered its tenants advantages to induce them to respect and maintain the conditions of cleanliness and decency provided for them. Among other things, it allotted an annual prize for the best-kept dwelling in each block.

The "Houses of Childhood"

But a far stronger inducement to cleanliness and good manners was afforded in those blocks to which are attached Case dei Bambini—literally "Houses of Children," but better, perhaps, "Houses of Childhood." The scope and influence of these institutions may be most briefly conveyed by reproducing some of the rules concerning them, which are posted in each block:

In the House of Childhood attention will be paid to the education, the health, and the physical and moral development of the children, by means of lessons and exercises adapted to their age.

All children of the block between the ages of three and seven have the right of admission to the House of Childhood.

The parents of children attending the House of Childhood pay no contribution whatever; but they assume the following imperative obligations:

(a) To send their children to the school-room at the specified hours, clean in person and clothes, and wearing a suitable pinafore:

(b) To show the greatest respect and deference toward the directress and staff of the House of Childhood, and to cooperate with the directress in promoting the education of the children. At least once a week mothers can speak to the directress, reporting their observations of their children at home, and receiving from the directress notes and suggestions for the good of the children.

Pupils will be expelled from the House of Childhood (a) who present themselves in an unwashed and stovenly condition; (b) who are not amenable to discipline; (c) whose parents fail in respect to the persons in charge of the House of Childhood, or in any way threaten to counteract by bad conduct the aims and the educative work of the institution.

In the assignment of annual prizes for the best-kept house, account will be taken of the way in which the parents have cooperated with the directress in the education of their children.

It is possible that the benevolent despotism of these regulations would not everywhere be appreciated; but there is no doubt that the Houses of Childhood are, and are felt to be, an immense boon to the class of people for whom they are intended. The school performs the function of a creche — takes the children off the mother's hands during working hours, and thus improves the economic position of the household— while, at the same time, it removes the chief difficulties in the way of domestic cleanliness and order. It is an inflexible rule that the directress of each school shall live in the block of dwellings that it serves, and keep in constant touch with the parents, who are free to come at any time and see "how their children are getting on." In this way, says Maria Montessori, "the school is placed in the home; it becomes part of the collective property; . . . . and the feeling of collective property is new, and sweet, and profoundly educative."

Edoardo Talamo, as director-general of the Real Estate Institute of Rome, placed Maria Montessori in charge of all the schools to be founded by his association, giving her full liberty to organize and govern them as she thought best.

On the 6th of January, 1907, in the Via dei Marsi 58, she opened the first Casa dei Bambini, and confided it to the care of Candida Nuccitelli, an instructress trained according to her methods and convictions.

On the 7th of April in the same year a second House of Childhood was opened in the district of San Lorenzo. On October 18, 1908, the Humanitarian Society of Milan instituted a House of Childhood in the workingmen's quarter of that city, and the House of Labor, belonging to the same society, undertook the manufacture of the didactic material used in the schools. At the villa of the British Ambassador in Rome there is a small school for aristocratic children; and two others have been opened in the Italian capital for children of the middle classes. They are all under the direct care and inspection of Maria Montessori, whose university title is Professoressa.

The most conspicuous of Maria Montessori's triumphs is that of teaching quite young children, without putting the smallest strain upon their faculties, first to write and then to read — for her method inverts the usual order in which these accomplishments are acquired. This end she achieved, as so many other great results have been reached, without foreseeing or aiming at it. To the children themselves it seemed that they had begun to write and read simply because they had "grown big enough." But, to render this comprehensible, we must enter a little more at large into Maria Montessori's principles and practice.

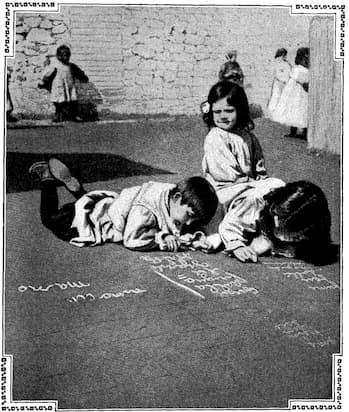

PRACTISING A WRITING LESSON ON THE PAVEMENT

MARIA MONTESSORI'S PUPILS FIRST BEGAN TO WRITE WITHOUT HAVING HAD A SINGLE LESSON IN ACTUAL WRITING. THE PREPARATION HAD BEEN SO COMPLETE THAT THE FINAL ACT CAME SPONTANEOUSLY, AND THE CHILDREN BELIEVED THAT THEY HAD BEGUN TO WRITE BECAUSE THEY HAD "GROWN BIG ENOUGH"

Maria Montessori Rediscovers the Ten Fingers

FITTING GEOMETRICAL INSETS INTO THEIR FRAMES BY RUNNING THE FOREFINGER, FIRST AROUND THE RIM OF THE FIGURE, THEN AROUND THE EDGE OF THE EMPTY SPACE.

At the very root of her method lies what may be called the rediscovery of the ten fingers. Put on the track by Seguin, she realized that the sense of touch, the basis of all the other senses, was the great interpreter of vision and guide to accuracy of perception. It was at the same time the earliest developed of the faculties and the first to be dulled if left uncultivated. She found that the finger-tips of young children are almost unbelievably sensitive, but that, in the absence of careful training, they begin to lose this sensitiveness after the age of six. The first step in her method, then, is to teach children to "see with their fingers," and thus to cultivate a delicately retentive muscular memory. Not only is this a desirable end in itself, but it has the further advantage of minimizing the strain placed by ordinary methods of education upon the eyes, and consequently upon the brain. By the cultivation of the sense of touch, reflex actions are set up in inferior nerve-centers with which the brain has little or no concern. One of Maria Montessori's chief objections to some of the most popular kindergarten employments is that they involve a harmful effort of the organs most closely associated with the brain — the eyes.

No sooner has a child entered the school than the education of his (or her) sense of touch begins. He is taught to wash his hands carefully in cold water, with soap, and then to plunge them into warm, clear water. In addition to this, the first and second fingers are plunged first into cold and then into warm water, and he is led to notice and to know the difference. The discrimination between rough and smooth comes next. This being an actual lesson, it shall be described fully, as it is the proper picture of the only form used in teaching in the Casa dei Bambini.

Learning the Difference Between

"Rough" and "Smooth"

TRAINING THE SENSE OF TOUCH

THE LITTLE GIRL AT THE LEFT IS LEARNING THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN ROUGH AND SMOOTH BY RUNNING HER FINGERS ALTERNATELY OVER COARSE SANDPAPER AND SMOOTH CARDBOARD. THE BOY IS LEARNING TO DISTINGUISH DIFFERENT SHAPES BY FITTING GEOMETRICAL INSETS INTO PLACE BLINDFOLD, GUIDED ONLY BY HIS SENSE OF TOUCH. THE CHILD AT THE END IS DISTINGUISHING TEXTURES BLINDFOLD.

Two cards are put down in front of the child — little Lucia, for example, who has seated herself comfortably in a nice, broad little chair, in front of her chosen table. One of these cards has a surface of satin paper; the other is of the coarsest black sand board. The teacher, taking the child's hand in hers, passes the tips of its first and second fingers over the smooth card. She must be careful to draw them from left to right, for the sake of the muscular memory, which, if not carefully considered, might cause trouble some future day. The tiny fingers like the contact. They continue to move along after the teacher has released them, and the child looks up, smiling. "Smooth," says the teacher, slowly, distinctly. If she adds one more word, even a term of endearment, she will transgress her duty, which forbids her to run the risk of confusing her pupil. To confuse is to tax the brain, and that is a cardinal sin.

If the little one continues to feel the card, the teacher repeats the word. But if the child's curiosity awakes, and it takes its fingers away and looks longingly toward the other card, then the two little fingers are passed gently over the sandboard. "Rough," says the teacher. The child doesn't like that feeling; she very likely draws her fingers away; but will soon tentatively put them back again. "Rough," the teacher will again repeat. Then the cards are taken and put down, side by side, for the child to look at them. "Give me the smooth?" asks the teacher. The child remembers at once the nice card, and hands it to her.

"Give me the rough." That, too, will be handed to her, with the air of importance which children can so deliciously and successfully assume.

The teacher smiles her thanks, and again the cards are placed on the table. "What is that?" she says, pointing to the satin card. "Smooth," replies the proud pupil. "And this?" The answer comes, "Rough."

Children Correct Their Own Mistakes

It must not be supposed the that answer is invariably correct, especially when the question concerns more difficult objects, as they will later on in the course of education. But the rule for the teacher is that, should mistakes be made, and the two objects (for there are never more than two at a time) be confused one with the other, she must not correct the child, but leave it to consider quietly, while she goes off to some other duty, not to return until another day, unless the child

demands her. This abstinence from correction is explained as follows:

Why correct the child? If she does not succeed in associating the name with the object, the only way of making her succeed is to repeat at once the action of the

sensorial stimulus, and the word to be associated with it; that is to repeat the lesson. But the fact of the child having made the mistake implies that at that moment she is not disposed to the psychic association which you desire to provoke in her; hence it is best to choose another moment.

No Naughty Children in the "Houses of Childhood"

In Montessori's view, all education worth having is autoeducation. One of the difficulties experienced in the training of teachers is that of preventing them from rushing to the aid of a child who appears to be embarrassed and puzzled in one of his little employments. Their tendency is to say, "Poor little mite!" and help him out; thereby depriving the child at once of the joy and the education of overcoming an obstacle. The policy of nonintervention applies, as a matter of course, no less to the moral than to the intellectual-domain. Rewards and punishments are rigorously banished from the House of Childhood.

The ideal of "discipline for liberty" is aimed at, and attained. The artificial rigidity and immobility of the ordinary school are entirely foreign to Maria Montessori's system. She even becomes sarcastic over the scientific desk and seat, carefully measured and fixed, of which modern educationists are so proud. It should not, in her view, be necessary to regulate the relation of seat to desk so as to avoid the danger of spinal curvature in the pupil. Her plan is to provide him with an easily movable and comfortable little chair, and never to keep him in one position long enough to feel even a temporary stiffness. The child, in her conception, ought to be free, within the limits imposed, not by scholastic convention, but by social amenity; that is to say, he must not use his freedom to hurt or incommode others. He must be taught to distinguish between good and evil, but not, as in the conventional discipline, to confound good with immobility and evil with activity. And, as a matter of fact, discipline presents little or no difficulty in the Houses of Childhood.

We have sometimes [says Maria Montessori] had to do with children who disturbed the others and were deaf to our admonitions. First we would have them specially observed by the doctor; but often they were found to be quite normal. We would then place a little table in the corner of the room, and seat the child at it, with his face to the others, giving him whatever he wanted to play with. This isolation would almost always succeed in calming the child; the sight of his companions would be a most efficacious object-lesson in behavior. Moreover, the isolated child would be the object of special care, as though he were ill. I myself, on entering, would first go straight to him, caressing him like an infant; and would then turn to the others and interest myself in their work, as though they had been men. I do not know what happened in their souls; but certain it is that the "conversion" of the isolated children was always definite and deep. They took a pride in knowing how to work and to behave with dignity; and, for the most part, they preserved a tender affection for the mistress and for me.

Such methods might prove dangerous in clumsy hands, but Maria Montessori is no less successful in educating teachers than in educating children. It was, of course, difficult at first to get them to understand her principles.

"What!" they would cry. "No corrections! No rewards! No punishments! Only individual influence! Why, we shall have anarchy, with our small spoilt babies doing what they like, not what we want them to!"

But the founder of the schools held her ground firmly; and the experience of three years or more shows that there is no anarchy, no disorder, in the Houses of Childhood. The teachers have learned the great lesson that tranquil nerves in authority beget tranquil nerves in subjection. They are women of broad mind, quick sympathy, and practical common sense, fully understanding the important difference between patience and indolent acquiescence. They know how to turn the current of discipline in the right direction, and to make the little ones understand, without reproof, the difference between good and evil. The bambini are so perfectly under control that they can be swayed by a gesture, as an orchestra is swayed by the baton of the conductor. When I said to Maria Montessori, "How do you manage to keep them so quiet and good?" she replied: "Because they are all doing what they like to do. Ecco!"

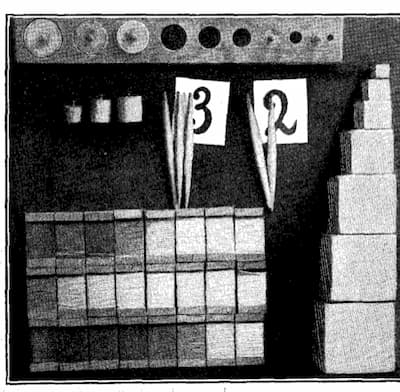

Children of Three Learn to Tie Bow Knots and to Fasten Buttons and Clasps

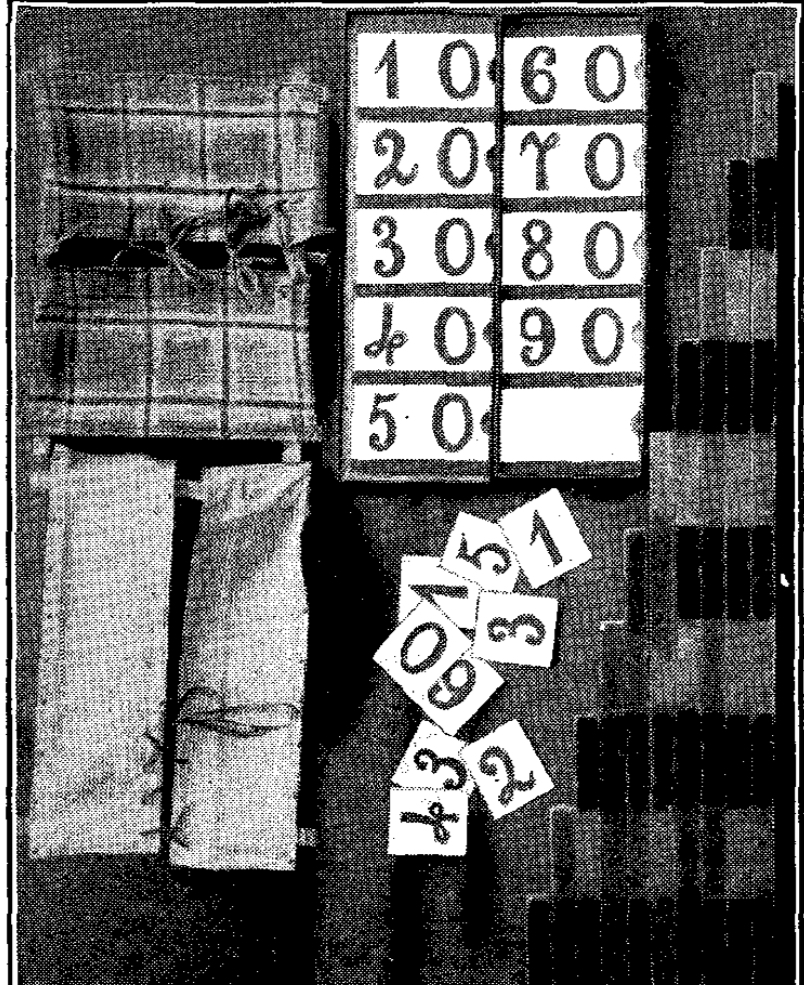

APPARATUS USED IN TEACHING CHILDREN TO TIE KNOTS, RUN LACINGS, ETC.; ALSO NUMBERING APPARATUS AND BLOCKS FOR TRAING THE CHILD ESTIMATE LENGTH

Let us now return to little Lucia, who has just mastered the difference between rough and smooth. Proud of her new accomplishment, she tries to attract the attention of a chubby little boy sitting at the next table, employed in fastening together two strips of cloth, attached to the opposite sides of a light embroidery frame, by tying them with bows of ribbon. He has been working unremittingly at these bows for some days, the teacher says; and, though he is only three years old, he has come to tie them so creditably that I, watching, could almost blush with shame to think of the hard knots that were all I could tie at the age of seven. When little Lucia holds up her cards, stroking them saying, "rough" and "smooth," he looks up indifferently, nods, and goes calmly on with his self-imposed labor.

Absorbed little Lorenzo is not the only one whose small fingers are learning cunning. Across the room can be seen several other embroidery-frames in the hands of children of various ages. From these frames hang strips of leather and strips of cloth. The strips of leather are provided with buttons and loops, and are to be fastened together with a button-hook. This toy is eagerly chosen, and always has claimants waiting in line for its use. There are other strips to be fastened together with corset lacings, or with the silk laces of bodices; others are for hooks and eyes, large and small. Again, we have buttons on cloth and buttons of pearl on linen; we have clasps and other sorts of fastening contrivances. These toys are a continual source of entertainment, to the boys no less than to the girls; and they are of such practical use that the mothers come, exploding in Italian manner, to say that little Nunzia or tiny Umberto now not only needs no help in dressing, but desires to assist in dressing the whole family.

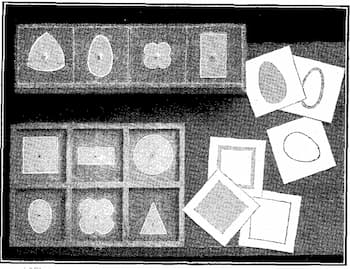

Recognizing a Circle or a Square

by the Way it Feels

SQUARE TABLETS OF WOOD WITH GEOMATRICAL INSETS WHICH THE CHILD LEARNS TO FIT INTO PLACE, AND SQUARES OF CARDBOARD CONTAINING GEOMETRICAL OUTLINES TO BE FILLED IN WITH CRAYON, ONE OF THE STEPS IN LEARNING TO WRITE.

A-small boy of the mature age of four, who has been sitting pliinged in either sleep or meditation, now starts up from his chair, and wanders across to his directress for advice. He wants something to amuse him. She takes him to the cupboard, throws in a timely suggestion, and he strolls back to his table, with a smile. He has chosen half a dozen or more thin square tablets of wood and a strip of navy-blue cloth. I stand behind him to see what he is going to do, but he does not notice my presence; he has more important business on hand. He begins by spreading down the cloth; then he puts his blocks on it, in two rows. They are of highly varnished wood, light blue, with geometric figures of navy blue in the center; there is a triangle, a circle, a rectangle, an oval, a square, an octagon. The teacher, who has followed him, stands on the other side of the table. She runs two of her fingers around one of the edges of the

triangle. "Touch it, so," she says. He promptly and delightedly imitates her. She then pulls all the figures out of their light-blue frames by means of a brass button in the center of each, mixes them up on the table, and tells him to call her when he has them all in place again. The dark-blue baize shows through the empty frame, so that it appears as if the figures had only sunk down half an inch. While he continues to stare at the array, off goes the teacher.

"Is she not going to show him how to begin?"

"An axiom of our practical pedagogy is to aid the child only to be independent," smiles Maria

Montessori. "He does not wish help."

Nor does he seem to be troubled. He stares a while at his array of blocks; yet his eye does not grow quite sure, for he carefully selects an oval from the mixed-up pile and tries to put it in a circle. It won't go. Then, quick as a flash, as if subconsciously rather than designedly, he runs his little forefinger around the rim of the figure, and then around the edge of the empty space left in the light-blue frames of both the oval and the circle. He discovers his mistake at once, puts the figure into its place, and leans back a moment in his chair to enjoy his own cleverness before beginning with another. He finally gets them all into their proper frames, and instantly pulls them out again, to do it quicker and better next time.

These blocks with the geometric insets are among the most valuable stimuli in the Casa dei Bambini. The vision and the touch become, by their use, accustomed to a great variety of shapes. It will be noted, too, that the child apprehends the forms synthetically, as given entities, and is not taught to recognize them by aid of even the simplest geometrical analysis. This is a point on which Maria Montessori lays particular stress.

It would take too long to describe all or one half of the educative games in use in the Houses of Childhood. It is worth noting that Maria Montessori insists strongly on the advantage of having a garden attached to each school, where the children can observe and foster the growth of plans, and where they can be instructed in the care of animals.

Wherever it is at all possible, the apparatus used in the Houses of Childhood enables, or rather compels, the child to correct his own errors -- to see at a glance whether his work "comes out" right or wrong. Maria Montessori also emphasizes the advantage of isolating the senses of the purpose of training. Education of the hearing, for example, may best be prosecuted not only in a silent, but in a dark room. Indeed, for training each of the senses other than vision, it is often advisable to blindfold the child. The senses of smell and taste she finds to be but little developed in childhood, and lays no great stress on their training. The sense of hearing can be and ought to be trained; but she finds that, while all children are sensitive to rhythm, only the gifted few have a keen perception of tone.

Maria Montessori's Pupils Able to

Distinguish Blindfold between a Grain

of Millet and a Grain of Rice

Some of the exercises of the sense of touch have already been described. The are of "seeing without eyes" is carried to such a pitch that blindfolded children can discriminate very find gradations of texture in stuffs, papers, etc. The sense of weight, too, and the "stereognostic sense," or power to distinguish solid forms by touch, are carefully cultivated, so that the children can tell a grain of millet from a grain of rice, and can distinguish one coin from another, though the differences between them may be very slight. All these discriminations are practices in the form of games, the other children sitting round in eager expectancy as to whether their blindfolded comrade will guess right or wrong.

APPARATUS USED IN TRAINING THE CHILDREN TO DISTINGUISH BETWEEN DIFFERENT WEIGHTS, COLORS, AND SIZES

For the education of the sense of sight the apparatus is somewhat more elaborate. There is, first, a series of games destined to train the vision in distinguishing dimensions. For instance (taking only those easiest to describe), the distinction between thick and thin is illustrated by a series of ten quadrangular prisms of equal length but regularly diminishing thickness, which the child has to range in their proper order, so that they form a regularly ascending stair. The distinction between long and short is illustrated by ten square rods of equal thickness, the longest of one meter, and the rest diminishing by a decimeter a piece. The decimeters are colored alternately red and blue, so that, when they are laid side by side in order, the colors form transverse stripes each a decimeter wide. Similarly, the distinction between high and low is illustrated by a series of gradually diminishing blocks, and the distinction between large and small by a series of cubes with which the child has to erect a pyramid or spire.

The discrimination of colors is carried to a high pitch by such games as the following: Colored silk of graduated shades is wound around card bobbins. There are eight fundamental colors and eight shades of each color — making sixty-four bobbins in all. Eight children sit around a table, and each chooses the name of a color. The sixty-four bobbins are then all thrown down in a mixed pile in the center, and the oldest child deals — that is to say, he (or she) picks out from the central heap the color demanded by each of his companions. If he makes a mistake, the deal passes to the next child on the right. When all the colors have been distributed, each child ranges his: eight bobbins according to the gradation of shades, and he who has first done this correctly deals in the next game. Many other sports of a like nature educate the color sense so perfectly that children, being shown a particular shade even of so elusive a color as gray, will cross the room and pick out the exact shade from a heap on a distant table.

LEARNING TO DISTINGUISH COLORS BY ARRANGING COLORED SILK ON CARD BOBBINS, ACCORDING TO GRADATIONS OF SHADE. THERE ARE EIGHT FUNDAMENTAL COLORS AND EIGHT SHADES OF EACH COLOR, MAKING SIXTY-FOUR BOBBINS IN ALL

The "Game of Silence"

One of MariavMontessori's most curious and valuable discoveries is the educative value of silence.

One day she happened to meet outside the schoolroom a mother with an infant four months old, swaddled after the Italian fashion. She carried the little mortal into the schoolroom, and held it up to the children, half jestingly, as a model of placidity, immobility, and noiselessness. As she enlarged on these characteristics, the imitative instinct of the children asserted itself, and they all fell to rivaling the baby in absolute immobility. The effect was marvelous; and, ever since that day, the "game of silence" has been one of the most popular in all the schools. The children, when the game is to be played, choose their seats. The teacher then goes quietly from one window to another, drawing the shutters together, until twilight reigns in the room. Some of the little ones always cover their faces with their hands. Others continue to wriggle and to move in their places until the whole room is nearly dark, and the teacher has retired to an open doorway leading into the vestibule. Then, like a coop full of young chickens going to rest, even the most uneasy ones gradually quiet down, and become expectant and serious, to await the ever-renewed mystery. When perfect silence has stolen over the assembly, so perfect that the ticking of a miniature clock in the room can be distinctly heard, the teacher calls a name, in a faint whisper: "Giovanni." Giovanni rises as quietly as he can from his little chair, and tiptoes out of the room into the vestibule. Woe to him if his small shoes creak! He must feel himself the object of some very black looks, for every one is trying to hear the name "Lucia," which is being murmured by the teacher. Lucia is more quiet in her movements than Giovanni. "Giuseppe," the teacher next softly calls, and a funny little boy silently joins the others in the hall. She continues to call in a mysterious whisper, until a dozen have stolen out noiselessly and solemnly. Then the game is over. Nothing that savors of prolonged mental tax is permitted to be continued for any length of time in the Houses of Childhood. Those who have remained in their places will get the chance to how how stealthily they can leave the room the next time the game of silence is played. When the game is ended, the shutters are opened and the school-room again flooded with sunshine. The little tongues begin to wag again. But this game has calmed all excessive excitability and restored placidity and tranquility. Sometimes they ask for it twice in the day. When one considers that the children of these schools belong to the most noise-loving nation in Europe, the success of this game is a greater triumph than the reading and writing.

The Mothers Beg Maria Montessori to

Teach Their Children To Write

Though it be only the inevitable outgrowth of her method, there can be no doubt that the teaching of young children to write, without the slightest strain or effort, is the most striking and impressive of Maria Montessori's achievements.

It was during the vacation of July, 1907, after the school had been opened for six months, that Maria Montessori was first induced to consider the instruction of children in writing and reading. She confesses to having been strongly prejudiced against the idea of putting such a strain upon the immature brains of children under seven. The first request came from the children themselves. Some of the more ambitious young aspirants to the higher learning arduously drew an "O" on the blackboard several times to convince her of their capacity. Then some of the mothers came to the directress in charge, to say that, as their children learned everything at the Casa dei Bambini without fatigue, they could not understand why she should refuse to let them read and write; in the elementary schools it would not be half so easy: "Little Guide, aged nine, at the public school, cried all the evening, whenever he had been forced to write that day." Maria Montessori, pursued by these persistent parents, at last wavered in her determination. The mothers even managed to make her feel as if she were neglecting a duty.

She demonstrates the utter irrationality of the ordinary method of making the child spend weeks and months laboriously drawing oblique lines, and then tagging a curve to a line, a line to a curve, and so forth. To teach a child writing through an analysis of its elements is, in her view, as absurd as it would be to teach a child grammar before allowing it to speak. Pot-hooks and hangers are the grammar of writing — an ex post facto analysis wholly unnecessary to the practice of the art. And, whereas a certain knowledge of grammar is necessary to one who would speak or write correctly, the grammar of writing is of no use whatever to those who have, synthetically, learned to write.

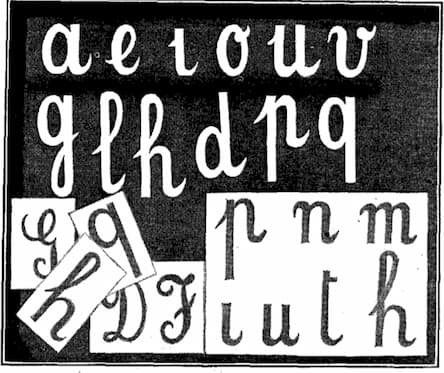

APARATUS USED IN TEACHING CHILDREN TO WRITE, CONSISTING OF FREE CARDBOARD LETTERS, WITH WHICH THE CHILDREN FORM WORDS, AND OF SANDPAPER LETTERS PASTED ON CARDS, WHICH THE CHILDREN LEARN BY TOUCH

The apparatus that Maria Montessori had used in training feeble-minded pupils to write was both expensive and in some ways unpractical. She had begun with letters elaborately carved in wood. Then she had devised colored letters pasted on pasteboard, which she taught her pupils to trace, first with the forefinger, then with the first two fingers, and finally with a little stick, to teach the motion of the pen. Although she succeeded in teaching some of these pupils with no more difficulty than was to be expected, there were many who were unable to follow the form of the letter without a control; and, for the same reason, these colored letters would not have answered for the auto-education of normal children, there being no means of selfcorrection for the finger, or of keeping it from slipping off the painted letter if the eye became inattentive.

She had labored at one scheme after another, without being satisfied with any of them. At last, one day, while she was absently superintending a first exercise with the cards used in discerning rough from smooth, the question solved itself in a flash of inspiration. That very evening, as soon as the children were dismissed, she, with her teachers, set to work to fabricate writing letters of large size and of coarse black sandpaper, which they pasted on very smooth square white cards. The letters were upright, in the clear round script now popular; and each letter was finished with a little tail to join it to the next letter. These cards, being very cheap, could be made in the great quantity needed. They were afterward supplemented by numerous letters cut out of paper, for laying on a table when the children tried to make words. The vowels were of pink and the consonants all of blue. A little strip of white cardboard pasted at the back of each of the letters precisely at the point where a guiding line would be drawn on writing-paper, enabled the little ones to correct themselves if, for instance, they were tempted to put the bottom of a g on a level with the base of an o.

The tablets with removable insets of geometric figures (mentioned earlier in this article) supplied the control and security with the pencil which Maria Montessori had found so difficult to teach her deficient pupils. All children love to scribble, and she determined to turn this passion to good account. She placed paper under one of the tablets, and, having removed the inset of a dark-blue triangle or oval from its light-blue frame, she showed the children how to fill in the figure by means of a dark blue crayon. The result was most gratifying. The children flattered themselves that they had made wonderful circles, ovals, and triangles.

At first shadings were very irregular and uneven, but the eyes that had learned to see soon corrected the pencils, and the dark-blue became smooth and even. When a pupil can fill in the figure properly under the control of the frame, he graduates to coloring figures that have only a pencil outline. Many can now fill -in such an outline without once letting their crayons slip beyond the pencil mark. This means full mastery over pencil or pen, and an ability to write without cramping the fingers.

Making Words with Cardboard Letters

MAKING WORDS WITH CARDBOARD SCRIPT, THE LESSONS IN ARTICULATION HAVE TAUGHT THE CHILDREN WHAT SOUNDS, AND CONSEQUENTLY WHAT LETTERS, ARE NECESSARY TO FORM THE WORDS

The children choose the letters they wish to learn. I and o are the most popular with beginners. When a child brings to the teacher the letter which he takes out of the box, he receives its duplicate in black sandpaper on a white card. The little one's finger is then drawn over the letter, from starting-point to finish, while the teacher says, "Touch it." The name of the letter is then repeated, distinctly and slowly. The child is encouraged to look well at the letters. Then the lesson pursues its usual course. "Give me t?" asks the teacher; then "Give me o?" Then she asks the name first of one of them, then of the other. That finishes the matter. They are not taught any of the capital letters until they have mastered the small ones, nor do they learn letters according to their regular succession in the alphabet. It is extremely entertaining to watch one of the little ones pick the letters out of the box. The child will peer into the various compartments and its little lips can be seen to move as it tries to hear with its inward ear the name of the letter desired. They have been pushed far on their way to divining by the exercise in articulation. Maria Montessori told me of a comical little chap of four whom she one day watched running up and down at play on the terrace. All the time he ran he was moving his finger in the air, while he half sang and half whispered: "To make 'Zaira,' you must have Z-a-i-r-a." After a few minutes he went to the box lying on the chair and picked out the letters correctly, immediately afterward lying down to spread them side by side on the pavement of the terrace.

Maria Montessori's Pupils Begin to Write

ONE OF MARIA MONTESSORI'S PUPILS WRITING FROM DICTATION AT THE BLACKBOARD. THE AVERAGE CHILD OF FOUR LEARNS TO WRITE IN SIX WEEKS BY THE MONTESSORI METHOD.

Without a Single Lesson in Actual Writing Although the pen-fingers of the children are trained by filling in the geometric outlines, and though not only their eyes but their muscles have become accustomed to some, at least, of the forms of the letters, the children do not yet know that they can write. They have, in fact, learned to write without writing. Even to Maria Montessori herself, the complete success of her experiment came at first as a surprise. The page in which she describes the first fulfilment of her dream is likely to become a locus classicus in the history of education:

"It was a day in December, an Italian day of winter sunshine. I was on the terrace roof, and the children were playing about or standing near me. I was sitting beside a chimney which rose above the tiled pavement, when it occurred to me to say to a little boy of five, who was standing by, 'Draw this chimney.' And I handed him a piece of chalk. He threw himself at once on the ground, and began to draw the chimney quite recognizably; wherefore, as was my practice, I praised him warmly.

"The little fellow looked up at me, smiled, was evidently on the point of bursting into some ebullition of delight, and then cried, 'Scrivo! lo scrivo!' ('I can write! I am writing!') Lying on the ground, he wrote on the pavement mano (hand), then, with new enthusiasm, he wrote camino (chimney); and, as he wrote, he continued to call out, 'I am writing!' so that the other children came running to see the sight, and surrounded him, staring in astonishment. Then two or three of them, trembling with excitement, said to me: 'Please! please! a piece of chalk! I want to write, too!' and, in fact, they set to work to write various words: mamma, mano, gino, camino, ada.

"Not one of them had ever had in his hands a piece of chalk or a writing instrument [except, of course, the crayon for shading the geometrical figures]; it was the first time that they had written; and they formed an entire word, as, when they first spoke, they pronounced an entire word.

"Thus did we go through the moving experience of the first development of graphic language in our children. During these first days we were filled with almost violent emotions, because we seemed to be living in a dream or witnessing a miracle."

Frenzy of Writing Takes Possession

of the School

"A veritable frenzy of writing took possession of our school. Each child flattered itself that it had detected within itself an especial gift of nature — a talent. Not being able to adjust in their little minds the connection between the preparations and the act, they were possessed with the amusing illusion that, having now grown to the proper size, they knew how to write — just as they had, when the strength came to them, been able to walk and to talk. This conviction shows clearly how little strain is put upon the tender brain by the preparatory work."

So great was the delight evinced, during the first few days, in this newly discovered ability, that the mothers came to report how, in order to save their floors, and even the crusts of their loaves, from inscriptions in chalk, they had been . forced to give their little ones paper and pencil; and the children, delighted and proud, not only wrote all evening, but took these treasures with them to bed, in order to begin again at daylight.

How essential is the part played by the tactile sense the following little example will show. On my first visit to one of the schools, while 1 was listening to an exercise in articulation, one of the older girls came up mysteriously to Maria Montessori, who was sitting beside me, and whispered some question. The directress turned away from me, and whispered two words that I did not distinguish. I noticed that she spoke slowly and carefully, and repeated one word three times. Away skipped the little inquirer, making some motions in the air as she ran toward the box of letter-cards on the table. She selected two, and hurried to the blackboard, which she could not reach comfortably without mounting on a chair. Then she wrote, "A greeting to Giuseppina Tozier," without mistaking a letter of the name. She only paused a moment to pass her finger over the two cards she held in her hand, on which were the capital letters G and T, in sandpaper. As the capitals are learned last, she was less familiar with them than with the small letters, and required to refresh her memory by touching them.

Children of Four Learn to Write in Six Weeks

The usual interval between the first preparation and the accomplishment of writing is, in children of four years, a month and a half; in children of five years the period is shorter, usually only a month; and one of the little ones learned to write, with all the letters of the alphabet, in twenty days. After either a month or six weeks, according to age, the average child writes all the simple words he pleases, and usually begins to write with ink. After three months most of them write well; and those who have been writing for six months are equal in their calligraphy to children of the third elementary class in the public schools. In fact, writing is the easiest and most graceful conquest of the bambini.

The transition from writing to reading is not so immediate as one might imagine. A child, no doubt, can always repeat a word that he has written; but, as Maria Montessori points out, this cannot properly be called reading. He is merely retranslating from symbols into sounds, as, in writing, he had translated from sounds into symbols. He already knows the word, which he has mentally repeated many times in the act of writing it. Reading, on the other hand, is the art of extracting a previously unknown idea from the written or printed symbols.

When a child composes a word with movable letters, or when he writes it, he has ample time to think and choose; whereas reading means instantaneously or very quickly interpreting the letters chosen and arranged by some one else. Writing, by the Montessori method, immensely facilitates the acquisition of reading — but it is not the same thing, nor are the two powers simultaneously acquired.

The Game of Learning to Read

In teaching to read, Maria Montessori banishes the traditional syllabary — the "a, b, ab, b, a, ba" of our childhood. What she does is to write in clear, cursive script, upon pieces of cardboard, numbers of words already well known to the children — for the most part, names of familiar objects. Whenever it is possible, the word, when once deciphered, is placed beside the object itself. And this is generally possible; for the Houses of Childhood possess most of the common objects of daily life, if not in full size, at any rate in the form of toys. No distinction is made between easy and difficult words. All words, in rationally spelled Italian, are equally easy to any one who knows (as the children do) the values of the individual letters; though the inexperienced eye, of course, needs longer time to decipher a long word then a short one. Very soon the children are able to take part in a reading game, thus conceived: All the most attractive toys of the school are displayed on a table; the name of each is written on a piece of paper, and the folded paper placed in a bag; each child draws a paper and opens it, without allowing any one else to see; and then, if he can clearly and correctly pronounce the word written on it, the scrap of paper becomes, as it were, a coin entitling him for the rest of the day to the toy inscribed on it. The success of this game surpassed the inventor's expectation; for it was found that the children declined to play with the toys, and preferred to go on drawing from the bag and reading the words!

The progress from single words to short phrases is effected by means of the indispensable blackboard. The teacher writes on it brief questions, which the children answer, or orders, which they execute — thus carrying on a sort of conversation, on one side in writing, on the other side in speech or action. For longer phrases an extension of the same method is employed. A number of different commands are written out on paper and distributed among the children -- commands of this nature: "Ask three of your companions, who sing best, to advance into the middle of the room; range them in a row, and sing with them any pretty song you choose." These papers the children take to their places, and con them in dead silence. Then the teacher asks, "Do you understand?" and when all have answered, "Yes," the word is given, "Then go"; whereupon the room, hitherto breathlessly still, is instantly changed into a scene of joyous bustle and activity.

This brief account leaves wholly untouched many of the most interesting and significant aspects of Maria Montessori's work — for instance, her dealing with numbers, her "first steps toward arithmetic." Especially is it impossible, within any reasonable limits, to convey an adequate idea of the solid and consistent philosophic basis on which her ideas and her methods rest. The application of her ideas to education beyond the infantile stage yet remains to be made. For the present, she has more than enough to do in recruiting a corps "of teachers, of disciples, of missionaries." There can be little doubt that, when this is done, the influence of her ideas will spread far beyond Rome and Italy, to "regions Caesar never knew." It may not be long before, in her own words, " the figure of the old schoolmistress, who labors to preserve the discipline of immobility, and wears out her lungs in a shrill and continuous flow of talk, shall have disappeared. For the mistress will be substituted a didactic apparatus which itself controls errors and places the child on the path of auto-education. The function of the mistress will then be simply to direct, patiently and silently, the spontaneous efforts of the children."

It is from American friends that Professoressa Montessori has met with the keenest interest, the deepest sympathy, and the most practical advice. To the encouragement of the Baroness Franchetti (Alice Hallgarten) and her husband is due her admirable book, "11 Metodo della Pedagogia Scientifica," in which Maria Montessori expounds the practical aspect of her work. Baron Franchetti, too, arranged for the international patent of the didactic apparatus that Maria Montessori has invented.

It was through another American, the Marchesa Ranieri di Sorbello, that the author of this article first heard of this precious boon to little children, and saw, in the nursery of her palano, two sturdy little sons who by its help had made a leap on the road of education several years in advance of their age. Without realizing that they had as yet done anything more than play, these two boys, the youngest of whom is only three and a half, can read and write both in English and in Italian.

A LESSON IN ARITHMETIC

Matt Bronsil is the author of these posts. He can be contacted at MattBronsilMontessori@gmail.com

<<< Back to the McClure article list <<<

Recommended McClure/Montessori Books

Montessori History Blogs

History of Montessori

Maria Montessori

History of Montessori in Taiwan

History

Mario Montessori

Mario Montessori

McClure's Magazine

McClure's Magazine

Montessori Video

Teachers TV: The Montessori Method

Read Old Magazine Articles

Old Montessori Articles

EFL and Montessori

EFL and Montessori